My ‘Camino’ experience was quite extraordinary in case you wanted to know.

I suppose that journey was rather the most exotic journey of any that I had ever taken in my lifetime. I have been to some faraway places, like Taiwan and Cuba, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, the Ayers Rock and Kyoto, but nothing can compare with my experience of walking for 850 kms in the north of Spain, carrying a heavy backpack and an even heavier burden of a lifetime of woes.

I have lived in Spain for 20 years now, and I suppose you could say that I speak the language pretty well. I did not need a visa for my Camino and I did not even leave the country that I had made my home so long ago, but what a strange place I encountered on the way. Ok, I have to admit that I have not done a pilgrimage ever before, but then I had not really thought of making this a pilgrim’s journey.

But nothing really prepares you for what you meet on the way and whom. I had chosen to walk on my own, in my own time, at my own pace. I think the Camino can not be taken any other way. Whether you are a pilgrim with a religious or spiritual purpose or whether you just want to test your own stamina and resolve, this is a task that is about one thing, and one thing only. It is about you and your life and your past and your purpose. That is what makes it so exotic and strange.

I suppose we go through life on an arrangement with ourselves to be comfortable. We live in a comfortable house, sleep in a comfy bed, eat food that becomes us, are surrounded by people that we feel close to and often even love dearly. We create a shelter that surrounds us. We create, and live in, a comfort zone. Fine. But on the Camino you leave all that behind. You say good-bye to the Comfort Zone.

You make yourself sleep in a different bed every single night. Not even a bed, but a bunk bed. You share your nights with people, sometimes people who you have never met in your life before. Some of them have habits and attitudes that you would not normally tolerate. You do not have the hot showers that you might be accustomed to. Some of the hostels afford no hot water. Some hostels are filthy. Some mattresses are plain right dirty. Surprisingly, this occurs often in shelters that monasteries might provide you with. Sometimes there is no hostel and thus, no bed, where your guide book led you to believe that there would be one.

Even the language can be a problem. Your entire Camino, if you do it the way I did, is along the Spanish coastline in the north, but people peak some strange idioms there. There is the Basque language, Euskera, which is not Spanish at all, not even Indo-European, which is spoken in the Pais Vasco. Then you get to Cantabria, which is o. k. Over into Asturias, where Spanish is spoken, unless you pass through a village or town where one speaks Bable, or another area where one speaks Eonavian. And then Galicia. The official language in Galicia is Gallego. If you end your journey in Santiago de Compostela at St. James’s cathedral, that’s it with all the confusingly different languages. But if you fancy to happen a bit further south, the Galician people start speaking Portuguese. You don’t need to show your passport along the Camino but you might as well have travelled through four or five distinct countries. And I started out from Mallorca, where one speaks a form of Catalán. Weird, really. Not comfortable at all, like you might think of your slippers as being comfortable, or the presence of your wife.

The secret of the Camino, to my mind, is really that you step outside of the Comfort Zone. You open yourself up to hardship, to uncomfortable nights, to quite a bit of bad sleep, interrupted by noise of which the snoring of your fellow pilgrims is only one. You ache. You hurt. You have blisters. You have reached the limits of your physical abilities. You sometimes go hungry and at times you run out of water. You get home sick, you miss your partner and your kids. You really don’t have a good time at all. You are wet most of the time because it is wet up there in the North. Either it rains, or you walk through the mist from the sea or from the low hanging clouds. Your clothes never dry. There might be a washing machine every ten days or so, and sometimes a tumble dryer. But do they work? No. You won’t get your clothes dry because it is humid everywhere and wet. And you walk. And walk. And walk some more, and lots. You don’t take the car, you don’t ride the bus, you ignore the train.

At home you might not walk the half a mile to go for a drink at your local pub or your morning Café Solo. But here you just walk and walk and walk. Sometimes you get lost, walking. Even though the Camino is marked you lose your way. Even though you follow a guide book you get waylaid and walk one or two or three kilometres more than you needed to. Some young person might have taken the signpost away or have broken it willfully, some other funny person might have painted the yellow arrow that accompanies you for four or five or six weeks and leads your way, in the opposite direction, just to spite you.

Then you meet this strange person, yourself. You begin to realize how weird you are. How strange your undertaking is, walking all these endless miles so far away from home. How peculiar this task is of walking to Santiago, and why? How very exotic the circumstances are that you find yourself in at this moment, and in fact, most moments of your comfortable life.

But the surprising bit is that you do not mind. You suffer the discomforts. And you get used to it all. You start thinking that everybody is quite silly to go by car everywhere when in fact it is so perfectly exciting to walk for a bit. You start realizing that you do not need a hot shower everyday of your life, and if you skip brushing your teeth, so what, once in a while. You begin to see people and companions as human beings that might have to offer you something despite their strange attitude or their weird behaviour. You begin to like this strangest person of them all, yourself. You make friends with yourself and your role in life, and your destiny. You start enjoying some discomfort and hardship and exhaustion because you begin to realize that you feel alive and perhaps more alive than you have felt for a very long time. Or ever. And that makes you feel at ease. That numbs the aches and the pain, the blisters and the exhaustion, the tiredness and the loneliness, the hunger and the thirst.

If you are lucky, as I was, you get to Miraz. After Vilalba you get to Santiago de Baamonde. In Baamonde you will be told that there wouldn’t be a shop or food or a bar or anything for a very long time. You had better buy some provisions. You are reluctant to buy too much because it will add to the burden of the weight of your backpack. By this time you really hate your backpack. But you have to buy some provisions, and then you set off.

Eventually, after a long, long walk, you get to Miraz. You enter the refuge. Something feels different. The hospitaleros do not seem Spanish. They hardly speak Spanish. Then you get it. These folks are English. British. You are being offered a cuppa tea. Then you are being pampered. You meet the nicest people you have met all along this Camino, and they speak your language. They think the way you do, and they make you feel at home. And because there is no shop around nor has there been for umpteen miles and miles, these kindly folks have set up a small shelf full of provisions. There are chocolate and biscuits, there are KitKats, there are pasta, rice, tunafish and other tinned food, tomato sauce and whatever. You can buy some food and drinks and cook your meal and have some more tea. And you can machine wash your clothes.

And the hot water works and the beds are clean. Blissful. All the suffering of the last three weeks or four is forgotten in an instance. This is one of the highlights of the Camino. At least it was for me.

The secret is that this refuge was taken over a year or so ago by The Confraternity of Saint James, in Good Old England. They have one more hostel, Gaucelmo, at Rabanal de Camino, on the Camino Francés, and they might open a third one soon on a different route if they can find one, and if they can raise the money. And these people show us how such a pilgrims’ hostel can be run and should be done. With love and care, and a cuppa.

Of course there is a drawback. They lie to you in Miraz. When I left the next morning David told me that the next bar or coffee house or shop would be a long walk of 15 kilometres. Well, that’s far from the truth. It was six hours and 20 kilometres, the longest and wettest 20 kilometres of my life. But thank you anyway, Caroline and David, for the best tea in ages and for the yummiest tunafish lasagna I have ever had. God bless.

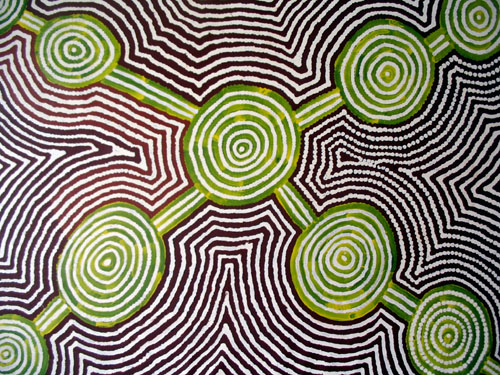

And thank you, Ramón, for the photo above.

You must be logged in to post a comment.